Marcos Cesar

Danhoni Neves*, Josie Agatha Parrilha da Silva**

Disturbing the Perspective:

The Church against the New

Perspective of Galileo and Cigoli

*Master’s Program in the Education of Science.

Universidade Estadual de Maringá (UEM). macedane@yahoo.com

**Arts Department. Universidade Estadual de Ponta

Grossa (UEPG).

josieaps@hotmail.com

Resumo: O presente trabalho avalia a questão

da perspectiva na obra galileana e seu impacto na nova arte da perspectiva no

renascimento e as tensas relações com a Igreja Católica.

Palavras-chaves: Perspectiva, Galileo,

Cigoli, relação ciência-arte.

Abstract: The perspective issue

in the work of Galileo, its impact on the new art of perspectives in the

Renaissance and the tense relationships with the Catholic Church are evaluated.

Key words: Perspective; Galileo

Galilei; Science-Art relationships.

Past products

of artistic activity are still part and parcel of the artistic scene. [...] In

Science, new things start with the abolishment of books and scientific

journals, now turned obsolete, and the elimination of their active stance in a

Science Library, removed to a barn [...] In contrast to Art, Science destroys

its own past. (KUHN, 1993, p. 370)

I. DA VINCI’S MOON

The relationship between Leonardo

da Vinci and the artists that succeeded him, which involve the

interrelationship between Science and Art, which, on its part, is still to be

understood, requires a survey on a very important theme: the tangibility of the

Moon by Science and by Art, as a dense, corruptible and anti-Aristotelian body,

welded to the four sub-lunar elements.

Believing that a work of art should

express total reality, Leonardo da Vinci was one of the most important

scientists who worked on the boundary between Art and Science. In da Vinci’s

opinion, it was necessary to limit the represented thing, the image, to its own

essence so that one could see further on:

[...] in his

opinion, the essential thing is the concrete and the immediate, the circumstantial

and the possible [...] Space, nature, perspective systematic analysis, sheer objectivity,

the value of experience, the “scientific” eye and the primordial hiddenness of

things strengthen his art through “hermetic totalities”. Through such attitudes,

da Vinci discovers [...] the soul’s passion for the boundaries of knowledge in

his transportation to the threshold of beauty (PRIETO & TELLO, 2007, p. 7)

“Primordial hiddenness” is da Vinci’s

motif to direct himself towards the natural comprehension of physical objects.

Such behavior is not common for a man of the Renaissance, still in its birth

pangs and blurred by the Aristotelian-Thomist architecture that poisoned all

and every world vision.

In da Vinci’s writings, extant in

the Leicester Codex and comprising his works on nature, weight and water

movements, curious notes on and sketches of the Moon, coupled to its light and

its nature, are given. Leonardo

states that “della luna – nessun denso è

più lieve che l’aria”.

Leonardo triggers an argument that

will lead him to the outskirts of Galileo’s thought. When he studies the lumen cinereum phenomenon, taking

precedence on Galileo by a century, da Vinci explains that the luminous

phenomenon is produced by the reflections of the seas, similarly to what occurs

with terrestrial seas and not by some intrinsic and autonomous phenomenon of

the lunar light (Figure 1). Da Vinci’s intuition perceives an irregular light,

non-homogeneous to the moon’s outlines, that separates the light section from

the dark one (in the first and last quarters)

Figure 1 - The lumen cinereum phenomenon

Leonardo’s doubt on the

moon’s nature “is whether the moon is a ponderous or light body”. He even

affirms, dangerously for an Inquisitorial age, that the Moon may have an

atmosphere similar to that of the Earth’s, in which physical laws must be the

same as for sublunar elements. “The Moon has water, air and fire and sustains

itself in space similar to the Earth, with its elements in another space. Thus

dense things do the same things as the Earth’s dense things do” (VINCI, 1996,

p.46).

An interesting

astronomic observation is reported in Letter 7B under the title “Della Luna”.

When Leonardo studies once more the issue of lunar luminosity, he reaches the

conclusion that its surface must be wrinkled:

Since the

Moon does not have its own light, its luminosity must be caused by other things,

(...) the pyramidal light is stored, whose pyramid is based on the sun; the sun

and its angle end up in the center of the Moon [...] The Moon’s surface is wrinkled

and its rugosity does not occur unless by liquid bodies moved by the wind, as

we see the Sun is mirrored in the sea by means of a few waves (...) It should

thus be concluded that the Moon’s luminous section is made up of water [...] (VINCI,

1996, p. 28)

Da Vinci’s technique,

which precedes the perspective already started by Giotto, Masaccio and Alberti,

is foregrounded in an atmospheric perspective or sfumato. Leonardo gives an effect of distance and breaks off the canvas’s

bi-dimensional space by a three-dimensional effect which was practically

non-existent in the old-fashioned aggregate space (PANOFSKY, 1927) of the

Middle Ages. In the latter case, objects are juxtaposed on the canvass’s

bi-dimensional space without taking into consideration spatial relationships.

Leonardo was always

interested with the perspective issue which, in its bi-dimensionality,

represented the feeling of depth and space. He therefore sought to understand

the function of the eyes: “Extending the outlines of each body, in proportion

to their convergence, we will bring them to a single point and the

above-mentioned lines necessarily form a pyramid” (VINCI, 2004, p. 107).

Da Vinci classified painting as a

science that triggered the study on perspectives or the science of visual rays.

Science would thus be subdivided into three perspectives: linear, color and

blurring:

[...] the

first deals with the reason of the (apparent) diminishing of objects when they

are distant from the eyes. This process is known as the diminishing perspective;

the second contains the manner colors vary when they are distant from the eyes;

the third and last explains how objects should appear proportionately less

distant in so far as they are more faraway (VINCI, 2004, p. 107).

With

regard to perspective, da Vinci explained:

Perspective

is nothing more than seeing a place behind a plain and transparent glass on

whose surface all objects behind the glass may be marked (VINCI, 2004, p. 108).

Leonardo gave practical examples,

such as that of furrows in a field (“points of flight”), so that one could

understand perspective: “Only on one line, out of all that reach the visual

power, intersection occurs. It does not have any palpable dimension since it is

a mathematical straight line which originates itself from a mathematical point

with no dimension” (VINCI, 2004, p.

110).

In his “Tract on

Painting”, Alberti had already explained the fundamentals of perspective (ALBERTI,

1966). The law of perspectives, or rather, an image representation that

simulated a three-dimensional space on a bi-dimensional surface, was already

known during the Italian 15th century. Light and shadows could be

modeled with the impression of three-dimensionality. The aggregate space of the Middle Ages definitely gave way to the space system or the da Vinci rilievo (HOHENSTATT, 2000).

This is where the Moon’s

description as a wrinkled body lies – the Moon as a spreader of light reflected

from the Earth, with the anti-Aristotelian stance of being a bed-fellow with

the geocentric Earth, according to the rules of that time. One hundred years

had to elapse for the invention of the “perspective tube” or perspicillum (GALILEI, 1987) by Dutch

artisans and its posterior perfecting by the scientific genius of Galileo

Galilei.

II. GALILEO

GALILEI’S MOON

Galileo Galilei, born on the 15th

or on the 19th February 1564, the latter date according to Vincenzo

Viviani, his disciples and biographer (BREDEKAMP, 2000), a day after Michelangelo’s

death, would re-invent the new post-Copernicus science from an improvement of

lens spectacles invented by Dutch artisans and sold as toys by the glassmakers

of Murano and Venice.

Galileo perceived that by means of

the “perspective tube” (Figure 2) he would analyze with more details the limits

of vision while placing it at the reach of the “visual pyramid” that reveals

more detailed information of the heavenly bodies.

Figure

2 – Galileo’s telescope.

Without almost no knowledge on the

basic principles of refraction, especially those by Grosseteste (1175-1253),

Bacon (1214-1294), Digges (154?-1595), della Porta (1535-1615) and Kepler (1571-1630),

Galileo (1564-1642) discovered the imperfection of the Earth that covered a

universe mistakenly centered around a non-fixed Earth.

Feyerabend states:

[...]

serious doubts [exist] as to Galileo’s knowledge of those parts of contemporary

optics which were relevant for the understanding of telescopic phenomena. [...]

Jean Tarde, who in 1614 asked Galileo about the construction of telescopes of

pre-assigned magnitude, reports in his diary that Galileo regarded the matter

as a difficult one, that he had found Kepler’s Optics of 1611 so obscure ‘that perhaps its own author had not

understood it’. In a letter to Liceti, written two years before his death, Galileo

remarks that as far as he was concerned the nature of light was still in

darkness. [...] we must admit that his knowledge of optics was inferior by far

to that of Kepler. (FEYERABEND, Against Method, cit. by ÉVORA,

1988, p.41).

In his workshop Galileo made improvements

in the construction of telescopes which up till then were full of spherical and

chromatic aberrations and directed the instrument to the heavens. He perceived

the total implosion of the Aristotelic-Thomist world: a moon filled with

craters, millions of stars, the satellites around Jupiter, spots on the Sun’s

moving disc and a strange configuration in Saturn.

In spite of his limitations in

Optics, in 1610, when he published the Sidereus

Nuncius, Galileo upthrusted the new physics that had already been revealed

since the publication of Copernicus’s De

Revoltionibus.

With regard to the invention of an

improved perspicillum Casati says:

When Galileo

points his telescope to the Moon, he sees it ‘as if it distanced two mere

terrestrial rays’ […]. Galileo consequently reports that the Moon’s surface is

not contaminated by the great spots seen at all times and from all places, but

also by other minor impurities that are visible within the boundaries between light

and darkness and which arise, change their aspects and disappear with the

growth and the diminishing of the Moon. [...] Galileo is not only an astronomer

[...] but a master in sketches; in fact, he knows everything on shadows and the

manner the shape of things is revealed by their mutations (CASATI, 2001, p.

163).

Galileo states

We have the same spectacle on Earth during

dawn: we see the valleys still not illuminated and the mountains around them

opposite the brilliant Sun. As the shadows of the earth cavities are made

smaller in proportion to the rising of the Sun, these spots on the Moon lose

the darkness in proportion to the growth of the luminous section. […] Not

merely the limits between light and darkness on the Moon are shown unequal and curved

but […] many brilliant apices are revealed on the Moon’s dark section,

[…]which, after some time, increases in size and luminosity (GALILEI

apud CASATI, 2001, p.164)

Figure 3 – Sketches

of the Moon in Sidereus Nuncius

III. LUDOVICO CARDI’S MOON

During the 1931 restorations on the

dome of Santa Maria Maggiori, Rome, a later work comprising the erasure of an

original picture of “The Assumption of the Virgin”, by Ludovico Cardi, the

Cigoli (1559-1613), was discovered (Figure 4). The fake part of the painting

corresponded exactly to the Moon on which the Virgin was stepping. The original

painting consisted of a Moon with craters exactly as that seen by Galileo in

his Sidereus Nuncius.

Galileo and Cigoli were great

friends as may be surmised by the latter’s letter to M. Buonarroti (CARDI,

1912; MATTEOLI, 1964):

With great joy I appreciate your arrival

among us, together with a bettering of our Mr Galileo and his miraculous

arguments on celestial news, which I immediately transmitted to Mr. Giambattista Strozzi, who is very much pleased with the

health of both..

[...]

If I may be of any service to you, will

you please have the pleasure of asking.

[...],

Lodovico Cigoli

Figure

4 - Cigoli; dome of Santa Maria Maggiore; “The Assumption of the Virgin”, by

Cigoli

Cigoli was an important

painter and, in a special manner, a great theorist in perspectives. Significant

references may be found in his Trattato

Pratico di Prospettiva. Similar to da Vinci, he was interested in the

formation of images by the eye, and he described them correctly (Figure 5), as

if in a dark chamber.

Figure 5 – Cigoli’s Trattato Pratico di Prospettiva

Cigoli’s work on the Santa

Maria Maggiore dome is so advanced that his successors and colleagues in

painting, such as Velazquez, Pacheco and Murillo (EDGERTON, 2006) were unable, after

several decades, to defy the Church’s status

quo, as the image of the smooth Moon, lacking all imperfections, reveals in

their paintings on the Assumption of the Virgin (Figure 6).

Cigoli received all his knowledge

during his artistic training from the Italian renaissance. The Renaissance reached

its peak in the 16th century and deployed defined contours,

perspectives, light and shadows to achieve the perfection of images. However,

at the start of the 17th century Cigoli is caught within the

transition phase between the Renaissance Art and Mannerism.

Figure

6 – “Immaculate Conception” by Velazquez

(1618), Pacheco (1621) and Murillo (1660)

When perspectives are analyzed in

the works of Cigoli (WOFFLIN, 2006), they do not fit within those used during

the Renaissance, with defined lines and from one or more flight points.

Perspective is the first conspicuous thing which, as applied in the

Renaissance, actually fails to fit in the works of Cigoli (Figure 7). When two

lines are drawn that converge to a determined point, the point of flight is

found and thus, the visualization of the horizon line achieved. Although the

point of flight lies at the feet of the Virgin, these elements seem to be

doubtful since they may simply represent the trapezoid base for the moon.

In spite of a reduction in

perspective effect, the picture confers a great depth which is achieved through

the disposition of several images at the same layer, softened by a decrease in

the lines that surround them and, consequently, a decrease of sharpness,

according to the image’s distance.

If in all Renaissance artistic

works perfection was reached through the representation of all details,

contrastingly Cigoli decreases his details within the images to which he desired

to gain more depth. Consequently, he uses color changes and light and shadow

effects in a somewhat different stance from that made during the Renaissance.

If Cigoli is the mature artist,

between the Renaissance and Mannerism, including his studies on anatomy, why

does his work shows an apparent regression in the art of perspective?

Perhaps this is not the right

question. The existence of a book by the French sketcher Huret (1606-1670) is

well known. It shows several applications of perspectives with special

reference to anamorphoses schemes. Geometric deformations of images would give in

certain angles the normal and three-dimensional perspective. Such art may be

seen in the false dome of Il Gesù in

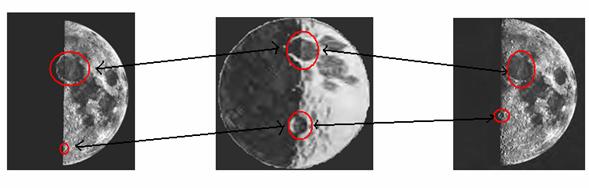

Figure

8 – Detail of Cigoli’s moon: left, as he painted it; center, the deformed

figure; right, the re-deformed and spherical moon.

Cigoli did not seek perfection in

his works but he merely desired to show the Moon as seen or should be seen by

the naked eyes.

CONCLUSION: HYPOTHESES ON THE

VARIOUS MOONS

According to the above, da Vinci believed that

the Moon could disperse light as the Earth does, through the activity of the

ocean waters, since he insisted that the moon’s surface was furrowed.

Whereas through his perspicillum Galileo encountered in the heavens the failure of the

Aristotelic-Thomistic world, his friend Cigoli painted on the cathedral’s dome

the Assumption of Mary on a moon as observed by Galileo.

The following comprise the issues:

i)

Did

Galileo provide a telescope with great spherical or astigmatic aberrations so

that Cigoli could paint the oval moon, far from the real thing? [It is known

through the deposition of Prof. Galluzzi of the London Warburg Institute that Galileo

spread various false evidences for the reproduction of telescopes so that

competitors of the recently established scientific field could be misled];

ii)

Are

Cigoli’s and Galileo’s moon actually equivalent;

iii)

Do

Galileo’s moons correspond to an almost photography of the Moon or is it merely

a pictorial interpretation?

Our hypotheses on the above issues

are:

i)

Galileo

was a friend of Ludovico Cardi and it would be very improbable that he gave his

friend an astigmatic telescope. Probably the oval moon is an anamorphic

technique to that by Huret;

ii)

Figure

9 shows a similarity of the two moons due to the presence of a big crater at

the right of the figure and on the left plateau.

Figure

9: Comparison between Cigoli’s moon (left) and Galileo’s moon (right)

iii)

Comparing

the Moon’s photograph, we may see that a) Galileo painted the terminator line

in a mistaken position; b) from the series of actual photographs of the Moon in

Figures 10 to 12, bw and false colors, displacement of the terminator line to

the left more than to the right, reveals a smaller crater than that reproduced

in Galileo’s sketch. It may be concluded that the crater has never been

reported since it never existed.

Figure 10 - Left, the moon in the southern hemisphere (first quarter);

center, the same photograph with deformed moon (oval); right, photo of moon in

the northern hemisphere

Figure 11 -

Comparing Galileo’s moons (center) with photographs of the Moon, with

displacement of terminator line. Above, moons in bw; below in false colors

(negative).

Figure 12 –

Comparing inexistent craters

Above hypotheses show

that Galileo’s artistic education as a pupil at the Academia del Disegno,

Such strategy failed and Galileo was

condemned to house imprisonment in Arcetri; Cigoli blurred his craters in an

undisclosed period and “corrected” the painting according to the old beliefs of

the Aristotelic-Thomist world. Perhaps Science and Art have encounter in this

episode their last respite.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We

would like to thank the administration of the Warburg Institute of the University

College of London for the use of Library; to the administration of the “Istituto

Italiano per gli Studi Filosofici” of Naples for the grants given for the Bruno

seminars in 2006 and 2007; to Dr Carlo Ginzburg with whom we discussed the Cigoli

painting and the Bredekamp article; to Dr Paolo Galluzzi of the “Istituto e

Museo di Storia della Scienza” of Florence for jis lectures on Galileo’s works.

REFERENCES

ALBERTI, L.B. 1966: On Painting. Yale:

BREDEKAMP, H. 2000: “Gazing

Hands and Blind Spots: Galileo as Draftsman”, Science in Context, v.13, n.3-4, pp.423-462.

CASATI, R. 2001: A Descoberta da Sombra,

CARDI, G.B. 1912: Vita di Lodovico Cardi.

CIGOLI 1992: Trattato Pratico di Prospettiva di Ludovico Cardi. Roma: Bonsignori Editori.

EDGERTON, S.Y. 2006: “Brunelleschi’s

Mirror, Alberti’s Window, and Galileo’s Perspective Tube”, História, Ciência, Saúde-Manguinhos, vol.13, suppl. Oct..

ÉVORA, F.R.R. 1988: A Revolução Copernicana-Galileana. V.II. Campinas: CLE.

GALILEI, G. 1987: A Mensagem das Estrelas. Rio de Janeiro: Salamandra.

HOHENSTATT, P. 2000: Leonardo da Vinci. Colônia:

Ullmann & Könemann.

KUHN, T.S. 1993: “Las Relaciones de

MATTEOLI, A. 1964: “Cinque

Lettere di Lodovico Cardi a

PANOFSKY, E. 1927:

PRIETO, A.G. e TELLO, A.

2007: Da Vinci. Barueri: Editorial

Sol 90.

VINCI, L. da. 1996: Della Natura, Peso e Moto delle Acque. Milano: Electa.

VINCI,

L. da. 2004: Anotações de Da Vinci por

ele mesmo..

WOFFLIN, H. 2006: Conceitos Fundamentais da História da Arte.

Posted:

February 5, 2008

Scienza

e Democrazia/Science and Democracy